The changing face of Test cricket

Daniel Laidlaw

When was the golden age of Test cricket? The late 19th century, or early

part of the 20th? The 1930s or 1960s? Or could it be the 2000s?

Some people like to glorify the past, claiming that certain players or

periods will never be matched. Sometimes they're right. And sometimes

they're not.

The differences between the celebrated days of cricket and today's supposedly gloomy times are marginal. In fact, the main difference between previous eras compared to today's, in terms of the attraction of positive

cricket, is the far superior over rates of yesteryear. Now, the mandatory 90

minimum is rarely exceeded, and more often than not extra time is needed

just to squeeze them in. That is the down side. But the positives outweigh

the negatives.

The differences between the celebrated days of cricket and today's supposedly gloomy times are marginal. In fact, the main difference between previous eras compared to today's, in terms of the attraction of positive

cricket, is the far superior over rates of yesteryear. Now, the mandatory 90

minimum is rarely exceeded, and more often than not extra time is needed

just to squeeze them in. That is the down side. But the positives outweigh

the negatives.

Test cricket is still a sport for the dedicated rather than casual fan, but

it has gradually reached a point where it has become a joy, rather than

merely an intriguing battle, to watch.

Notwithstanding the lopsided result, I would defy any two teams to produce a

spectacle as thrilling as that witnessed in the recent first Test between

England and Australia. From the last session of day 1 to the end of

Australia's first innings on day three it was Test batting, against an

attack which at least has to be classed as respectable, at its finest.

How much of the attractive cricket seen today can be traced to one team,

Australia, deciding to give new meaning to positive play and how much to the

general evolution of the game and the way it is played? It is in this area

where the insidious influence of one-day cricket, rightly maligned in a lot

of cases, has to take some of the credit. Today's player, with his surfeit

of one-day experience and conditioning to the abbreviated form of the game,

is much more comfortable with attacking philosophies. One-day cricket has

helped to teach players to score quickly and maximise every run-scoring

opportunity.

The instinctive running between wickets now seen when a ball has seemingly

been played into the close field can be traced to the necessity to score at

every opportunity in limited-overs games. That is a positive. So too is the

athletic and often spectacular fielding, a progression which was surely

expedited by the emphasis placed on saving runs in one-dayers, where the

benefits to be gained from such skill were more readily quantifiable. The

effect of a diving stop or crucial run out made with just a handful of runs

required to win is immediately recognisable.

Because of the amount of one-day matches played, it has become easier for

free-flowing batsmanship to make the transition to Test cricket. But as far

as aggressive captaincy and bowling is concerned, the opposite is true. Far

from the dull containment of one-day matches, Test field settings have

recently imitated those of previous eras when wickets were reportedly sought

with attacking field settings even when the batsmen were dominating.

The sacrifice of runs in the constant search for wickets increases the

attractiveness of the contest considerably. It should never be artificially

enforced, though, for the situation of the game should always be allowed to

dictate. Sometimes there is no other option but to attempt containment, and

that can be just as fascinating as it is fraught with danger for the

fielding side.

In all sports, the most successful teams are always copied. The methods of

the trendsetters are scrutinised and then emulated until another daring and

successful method is devised, and the process repeats itself.

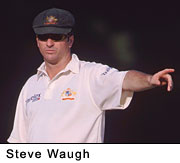

One person, Steve Waugh, must take a lot of credit for this, but consider a

few of the principles Australia has adopted:

Bowling first after winning the toss;

No nightwatchmen;

Aiming to score 300 per day, with innings run rates often between 3.5 and 4

runs per over.

Since cricket began, it has always been customary to bat first. The famous

line went something like: "If you win the toss, bat. If you are unsure,

consult a colleague, then bat." As he keeps stating when interviewed by

quizzical commentators at the start of each match, Waugh says simply that 20

wickets are required to win, and the best chance of achieving that is by

bowling first. It helps to have a fearsome fast bowling arsenal, of course,

but you can see his point.

Such risk-taking requires a team of enough quality and potency to make it

work. Australia is fortunate enough to field one, and has single-handedly

undertaken many recent initiatives. South Africa is another, but mostly they

elect for the traditional safety-first approach. With naturally free-flowing

batsmen, Pakistan and India could and often do play in that fashion, like

when India defeated Australia, but for teams of lesser talent it could prove

difficult. Eventually, if it remains successful, it has to catch on.

Such risk-taking requires a team of enough quality and potency to make it

work. Australia is fortunate enough to field one, and has single-handedly

undertaken many recent initiatives. South Africa is another, but mostly they

elect for the traditional safety-first approach. With naturally free-flowing

batsmen, Pakistan and India could and often do play in that fashion, like

when India defeated Australia, but for teams of lesser talent it could prove

difficult. Eventually, if it remains successful, it has to catch on.

Generally the best team of any era will determine how the period is

remembered. In the 80s it was the West Indies and their hostile pace attack.

In the late 90s and early 00s, Australia is making a powerful argument for

this era to be considered one of the golden ages of Test cricket. Before you

dismiss that, consider also that the greatest series, eras and players are

never properly appreciated in the present. Usually, they are only defined as

great in the fullness of time when they can be recalled and judged in

context.

It is quite possible that 1999 to 2009, if it continues at this rate, will

be remembered as one of Test cricket's best decades. The series, matches and

individual feats of the past two years have, with some notable exceptions,

been truly memorable and as fascinating for the cricket follower as at any

other time. Examples can be found in Tests between India-Pakistan,

Australia-Pakistan, Australia-West Indies and India-Australia.

Now, it is to be hoped that the positive aspects of Australia's style of

play (the attacking batting, bowling and captaincy, not the overt aggression

and sledging) are adopted by the rest of the world. Happily, it is gradually

being realised the best chance of defeating them is by embracing a similarly

positive approach. When that occurs and more teams discover the heights Test

cricket can reach when played in that vein, hopefully they will not want to

play it any other way. There is no more glorious cricketing spectacle than a

Test played in the right spirit by both teams.

Like Sri Lanka's approach to one-day batting in the first 15 overs,

Australia's strategy could revolutionise the way the majority of Tests are

played. Even if it is not taken to their extreme, like Sri Lanka's efforts

at the 1996 World Cup could not be consistently replicated, it could still

change the methodology in most matches.

We're at the beginning of a golden era in Test cricket. It's just a matter

of time before it's appreciated.

More Columns

Mail Daniel Laidlaw